"You serve your community by developing your talents."

Six dos and don'ts I learned this week to foster calm

Give yourself the first hour of your day

I found my name at the Letterpress

3 ways to capture your best headshot

Let Your Hands Decide For You

3 Ways to Expect More From Your Art

Guest Blog: How actor and writer Brynn Baron deals with rejection

Who Are You Becoming?

Jack Straw Writers tell "Family Secrets" at Literary Arts on October 2

I'm now Editor at 'Professional Artist' magazine

Ask your questions, while you still can

Apply for a residency or make your own

Let Yourself Arrive

After you walk to the podium or step onto the stage to read or give a talk “let yourself arrive,” said Elizabeth Austen, at the performance workshop I attended last Sunday at Jack Straw Productions in Seattle. Don’t rush, especially at the beginning, she said, because “it takes the audience a few moments to tune its ears to your voice.”

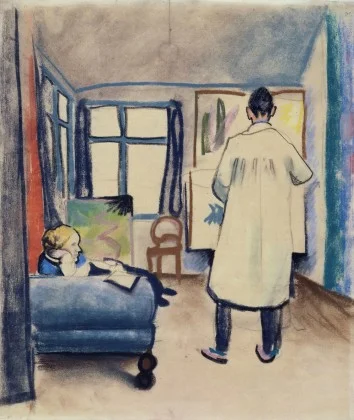

Austen is a poet, trained actress, Washington State Poet Laureate, and an inspiring, insightful performance coach. She has a knack for bringing out the best in the poets, memoirists and novelists among us – twelve writers reading in different genres, with different presentation styles, and different needs for each piece of writing. She helped us identify our natural gifts as performers and our challenges with many tips for how to “best serve the work.”

If you live in Seattle and want to see how this year's Jack Straw Writers applied Austen's coaching to our work, please join us on May 2, 9, or 16 at 7 pm at Jack Straw Productions. (I'm reading May 9 and would love to see you there.)

I want to share three more tips with you from Austen’s workshop that may help you when you rehearse for a talk or a reading:

“You are not the work,” she said. The performer you is different than the writer you (or the artist you). The way I think about this is when I’m reading a work or giving a talk, it’s as if I’m playing me in a movie. But it’s not “me.”

You’re performing (or presenting) “in service of the work,” she said. Think about what style will best serve your audience and your work. For example, you may be a shy person but your work may be large and loud. Can you stretch yourself as a performer so you can be as big as your words need you to be?

“Don’t let the word ‘perform’ scare you,” she said. “To perform is to activate, to bring something to life.” That’s all and that’s everything.

The gold to be found in rejection

Another rejection letter landed in my mailbox recently and I didn’t toss it in the recycling bin as quickly as I used to. Instead, I read it carefully. Because I’ve learned that you never know what gold you may find. It used to be that to rid myself of the sting of “no” I would scan the letter and throw it away almost in one motion. I wanted to rid myself of that rejected feeling asap.

Then, once, as I was skimming, I read this sentence: “We encourage you to apply again next year.”

Hmmm. I thought. “I bet they say that to everyone.”

I decided to find out if they did in fact write that to everyone so I called the organization. After thanking them for reviewing my application, Isaid, “I’m just wondering but did everyone receive the same rejection letter? Because mine encouraged me to apply again next year.”

“We had two rejection letters we sent,” the woman said. “So you received the better one.”

This wasn’t the acceptance I wanted but this meant a lot: it was encouragement to keep going. It was an invitation to look at my work again. It was what all artists want: an audience.

Here’s a few sentences from that last rejection I received:

We received more than 1,500 applications and can offer 40 residencies. Though your application did not advance into the final round this year, we want you to know that your work resonated with our reviewers. Sending work into the world is an act of bravery, and we appreciate the opportunity to experience your voice.

I didn’t need to call them this time.

Of course I was sorry to lose but this letter provided some gold. First, it showed me just how stiff the competition was this year. Second, it complemented my work and acknowledged my bravery. That took the sting out, and even better, propelled me back to the writing desk.

Also, I made a mental note for the next time I need to write a rejection letter: What I write can either open up a relationship or shut it down. Because of this organization’s nice letter, even though they rejected me, I still feel warmly toward them. Perhaps I’ll take a workshop with them or, when I’m feeling generous, give them a donation. In other words, they haven’t lost me.

The bus is my new editing suite

Where's Your Sword?

The Tomato That Saved My Creative Life

Persistence Pays Off

When I saw the call to apply to the Jack Straw Writers Program last fall, I almost didn’t apply. Why?

Because I’d applied every year for the last six years and I was tired of getting rejected. The closest I’d come was being wait-listed a few years back.

Then, I reminded myself what I tell my coaching clients: If you don't apply, it's a 100% guarantee you won't be accepted. If you do apply, your chances are better.

I opted for slightly better chances. Then, I rewrote my artist statement, edited the strongest writing sample from the memoir I’m currently writing and like every year, I mailed it by the deadline.

The twelve Jack Straw Writers receive voice/microphone training, recorded studio interviews, do a series of public readings in Seattle all year long, publish an anthology and are featured in SoundPages, the Jack Straw Literary Podcast series.

When the skinny letter from Jack Straw Productions arrived in my mailbox, I sighed. Everyone knows that if you win, it’s usually an email and that if it’s a letter, it’s usually a fat letter.

I opened it.

The first word after “Dear Gigi” was “Congratulations!” I’m now one of 12 writers chosen out of a pool of 93 applicants who will be in the Jack Straw Writers Program this year. This win was especially sweet because I’d included an excerpt from the memoir I’m now writing.

What did I learn? I learned what I teach my students: If you know an opportunity is the right match for you and the curator changes every year, it’s a numbers game. Chances are that one year, it’s all going to line up: The right curator for the right work sample out of the right pool of applicants.

This win also reminded me how important it is to receive recognition. I’ve had mostly rejections this year and this one acceptance has already fueled my writing. It’s also softened the rejections I’ve received since.

The next day, I received a rejection from the Hedgebrook Residency, one I’d love to attend. Their odds are even worse. They received 1500 applications for 40 slots. The silver lining: My rejection letter stated that my work “resonated with our reviewers.” They didn’t have to say that and I so appreciate they did.

You can bet I’ll apply to Hedgebrook every year from now on and one of these years, you never know. I might be one of those 40 writers.

So, I ask you: What’s an opportunity you know is the right match for you that you could “show up for”? It’s hard to keep showing up if they’ve already said “no.” But if you really want it, can you humble yourself and throw your name in the hat again and again? This year, it might be you.

Four keys to making creative progress

This past year, I embarked on writing a memoir and I learned how much more challenging it is to work on a big, multi-faceted project than something short. To write an essay, I just need to sprint. I have the whole essay in my head as I’m working on the beginning, middle and end. But a memoir with its many chapters and multiple re-writes is a full-length project that requires the stamina of the long distance runner. I can use my sprinting talent for individual chapters but to keep the whole project going, I must pace myself.

These four lifesaving actions have helped me this past year stay on task and on schedule. They’ve been:

Name “it”

Put “it” on a calendar

Hire a midwife/coach/mentor

Schedule weekly check-ins for creative support

Name “It”

In my 20 years as a writer, I’d written stories, essays, vignettes, monologues, poems, plays, solo performances, and then one day, the clouds parted, the shaft of sun descended and I knew I needed to write a memoir in book form. This realization was life changing. I re-arranged my work schedule to fit in 2-3 hours a day of writing and added other support. But naming it first was key.

Put “It” on a Calendar

Once I’d written for a couple of months, and collected all I’d created over the past 20 years I felt overwhelmed. I didn’t know which stories fit where or even how many stories there were. So, I sat down with a production manager, counted the number of stories I had or could write, and gave myself a goal of finishing a certain number each week. I put a reminder in my calendar every day. Then I gave myself a deadline for delivering this rough, unfinished draft to my next key support: my literary midwife.

The calendar turned out to be magical. Committing the project to paper made it happen. Even when I couldn’t quite keep up with my weekly schedule, the rough draft was done by the time the deadline arrived, as if a force greater than me was pushing it forward once I committed it to paper.

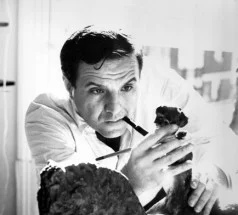

Hire a Midwife/Coach/Mentor

My literary coach is not a friend, although I like her and admire her writing. Her not being a friend is important for me because it makes our working relationship feel more professional and therefore less possible for me to wiggle out of my commitment. Also, I’m paying her which makes me take it seriously. I won’t pay for something and then not use it. It forces me to deliver the goods. I know she believes in me but I know she has high standards. So her voice in my ear as I write, keeps me writing and striving to do my best. Which is why after all this sustained effort I need something cuddly. This is where my two colleagues come in.

Schedule weekly check-ins

I scheduled short weekly check-ins with two artist friends. With these cohorts I can complain, stomp my feet, share my successes and burn off a lot of neurotic ramblings that I don’t want to submit my literary midwife to. My friends cheer me on, no matter what. Their cheering gets me back to the writing desk every day.